See These and Other Posts on Instagram

Competing in sports is not the same thing as skydiving. In skydiving you may be legitimately afraid that your parachute might not open (that is why it is checked multiple times) because if it doesn't open that creates a very serious outcome.

What's the outcome for you if you don't win a sport competition? You will feel disappointed; you may feel sad; and then, on the other side of those feelings, you will BE OKAY.

Interestingly, for numerous athletes their fear of not winning is not about them, it's about other people. They don't want to let other people down. They don't want to be viewed as less important by other people. Why are you giving these other people power over you?

The people whose support you want in your sporting life are the people who only expect one thing from you when you are in an actual competition: that you fully invest, battle, and compete. That's the only box you have to check.

Now, when you are preparing for a competition it is completely appropriate for the people in your sporting life (e.g., your coaches) to expect that you do everything you can to raise your level of proficiency (think back to the importance of skydivers checking their parachute multiple times and knowing what to check). This determined attention to detail and engagement in training will serve you well in competition (and technical/tactical reminders can also be helpful in competition). But when it comes to your approach to the actual competition it's just about giving it a go! 😀

Belief change starts with you. As an athlete it is important that you believe you have the ability to reach your potential - no one can believe it for you.

Here are some research findings to help you, if for some reason, you currently don't believe you have the ability to reach your potential. The number one causal factor dictating how close an athlete will get to their athletic ceiling is the level of determination (grit) they bring to their journey of trying to become as good as they can be. In fact, research has shown that what people eventually accomplish may depend more upon their passion and perseverance than on their innate talent.

When I meet with athletes who struggle with self-belief I often ask them to consider the following scenario: a movie is being made about their sporting life, and everyone involved in their sport journey is meeting together in a meeting room to discuss the development of the movie. I ask the athletes to tell me who is sitting at the head of the table leading the meeting. Sometimes athletes name a particular coach, or a parent. Often athletes don't mention the person they should be mentioning - themselves.

As the athlete you are at the head of the table. It is your call to decide if you want to try and get as good as you can get; it is your call to decide if you believe you can get as good as you can get; and it is your call to decide how determined you are going to be to try and get as good as you can get. It is not a straight-forward journey - there are good days and tough days. I wish you well on your journey (and I support you completely if you decide to direct your passions elsewhere). I am also always available to help regardless of what you decide 😀.

Now you know what post-secondary coaches look for when they are scouting athletes. They first want to know if you have the ability to play after high school. Unfortunately, that is all most athletes think about.

What post-secondary coaches also want to know is do you have the character to pursue your best self in your sport? Do you have the work ethic, passion, and drive? If you focus on the character you will put in the work to maximize your development, and you will give yourself the best chance to not only play after high school, but to maximize your post-secondary sport experience. 😀

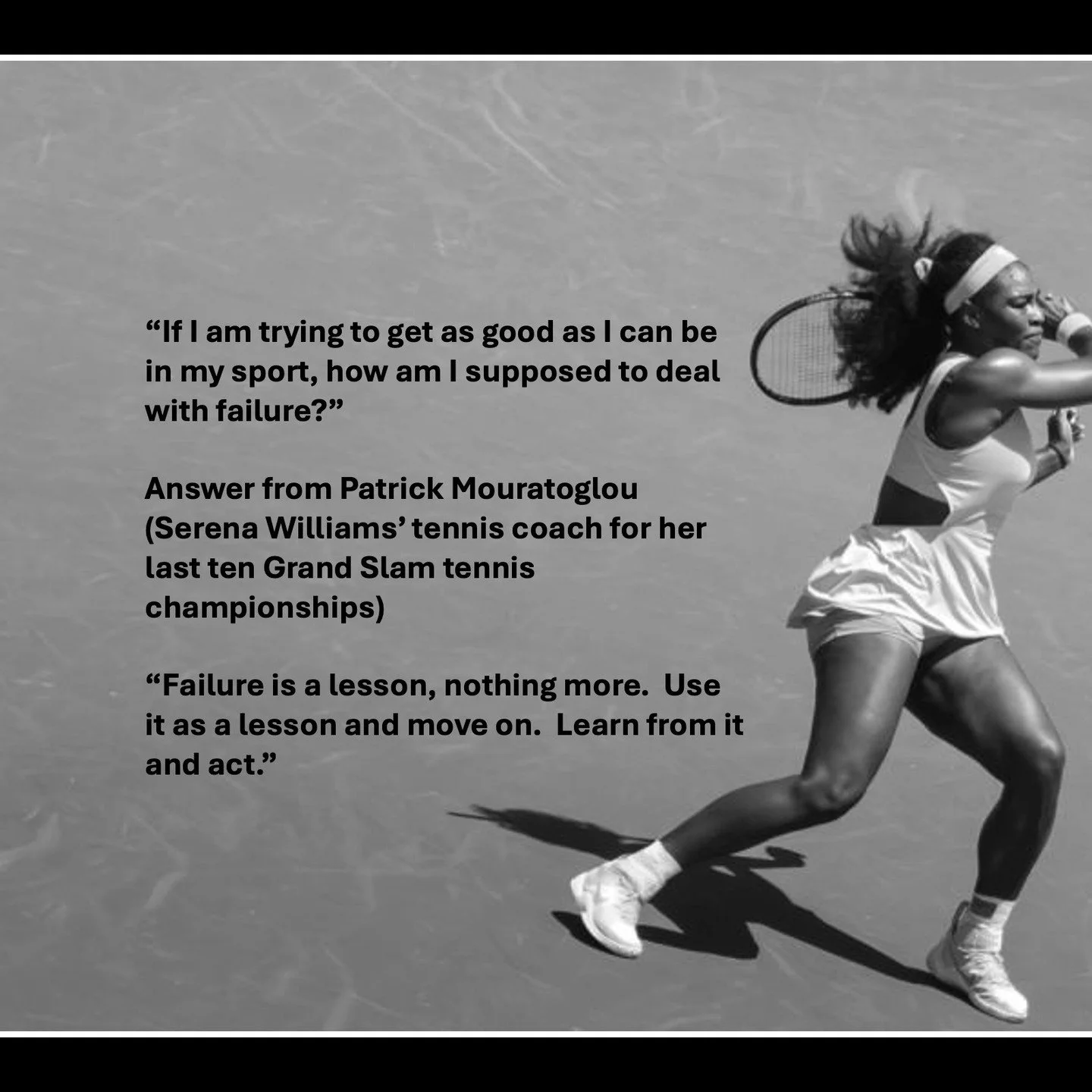

Good advice! Serena Williams dipped to 175th in the world rankings BEFORE she won the first of her last 10 Grand Slam championships. She won 23 Grand Slam championships overall, but experienced significant times of failure along the way. Failure is an experience NOT an identity. Learn from it and keep on pursuing your best self in your sport 😀.

When some card games end in a tie, some people use a single card draw to break the tie. Simply put, whoever draws the better card (e.g., a 10 vs a 4) wins the game.

Some of the most challenging sport mental training work is to help athletes understand that a won-loss record doesn't function like a playing card. Just because one team has a better won-loss record than their opponent doesn't mean they will win the competition against their opponent.

In fact, a team's won-loss record has NOTHING to do with whether or not they win a competition. Whichever team PLAYS AT A HIGHER LEVEL will win the competition. As seven-time Super Bowl champion Tom Brady stated: "...it's the team that plays the best that wins. I was a part of a team that won every game until the Super Bowl, and we didn't play the best that day and we lost...".

Athletes, please remember that won-loss records have NOTHING to do with winning a competition. Level of execution and investment has EVERYTHING to do with winning a competition. In training, work diligently to raise your level of execution. In competition, fully invest, battle, and compete, and your training will serve you well. 😀

When our boys were young my wife and I took them whitewater rafting. It was a group adventure involving a series of rapids that were mild in nature but still exciting to go through.

Early in the adventure our oldest son fell out of the raft between two sets of rapids. He wasn't in harm's way, but I got out of the raft, swam to him, and helped him back into the raft. Problem solved, but in the process of helping my son my sandals fell off and disappeared into the river.

Our journey continued and on two occasions we were required to carry our raft on two lengthy portages around two sets of rapids that were too extreme to go down. Both portages were on gravel paths littered with sharp and pointy rocks. These portages were no issue for the people with footwear, but as I navigated them in bare feet I was in significant pain and discomfort.

Being the "Dad" I didn't say anything. I just soldiered on but it dawned on me that no one knew the pain and discomfort I was experiencing because they all had protective footwear on their feet. This is the connection to being a good teammate.

There are times in all of our lives when our sandals are off and we are dealing with tough stuff. In those moments we need to reach out for help, and we need people who have got our back. As a high-performance athlete trying to get as good as you can get in your sport has its moments of challenge and grinding. In a team sport we need our teammates with us taking on the challenge together. We need our teammates to be sensitive to the fact that "the problem may not be the problem" if we are struggling in the sport, and we need to know that they've got our back - particularly in those moments when our sandals are off. We also need to know that we can reach out to them for support instead of suffering in silence. When teammates collectively take on the challenge of pursuing their best selves in their sport, and are there for each other in good times and in bad, the sky is the limit! 😀

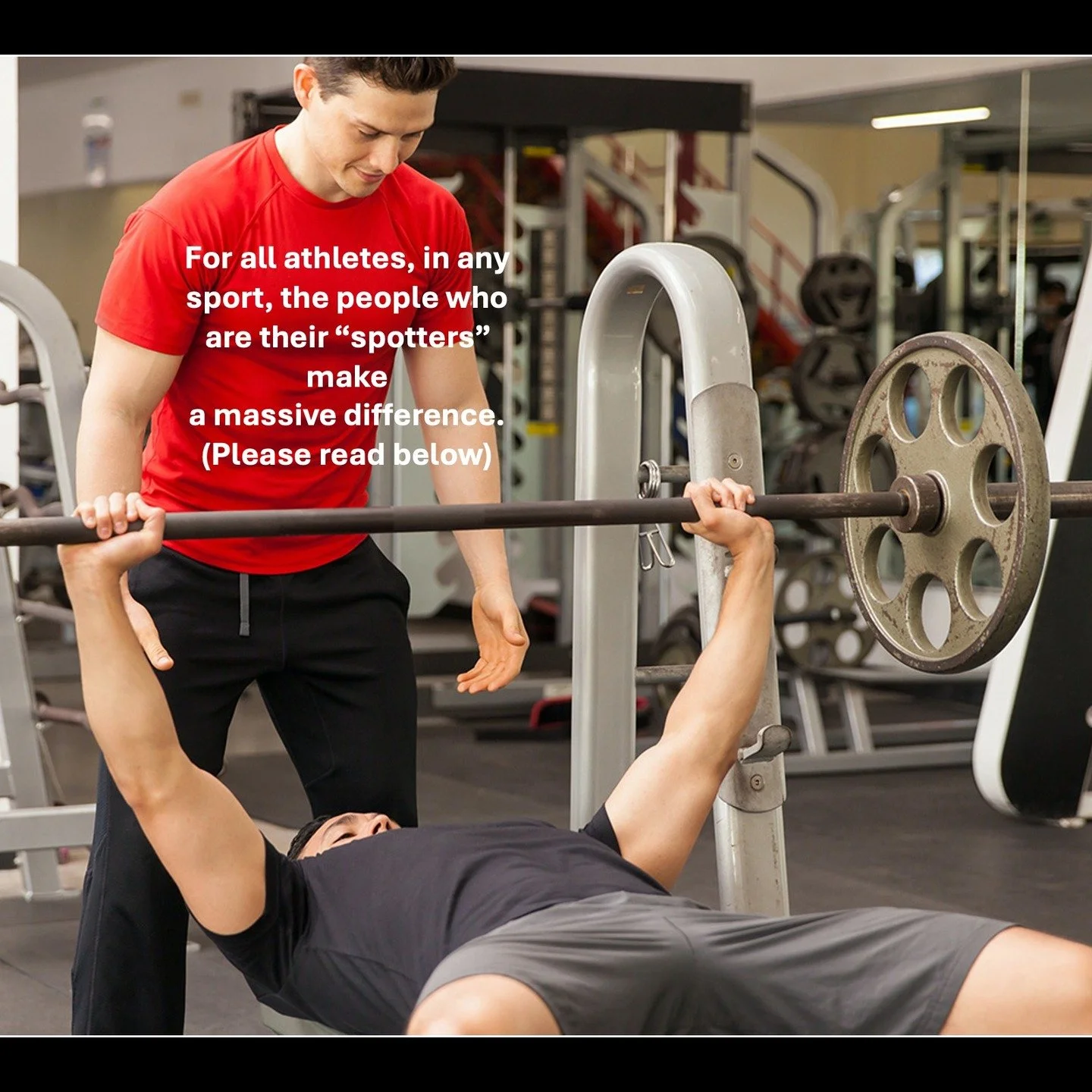

Every high-performance athlete wants to raise their level. If they don't they shouldn't be in high-performance sport. How do we, as coaches and teammates help them do that? Embrace a significant research finding from the world of strength-training.

Assuming an athlete has been diligent in their training, if you want to help them set a personal best in the bench press the most important thing you can provide them with is a spotter. Think about the spotter's role - they bring three key components to the athlete's bench press experience. They encourage the athlete ("you are capable of this"), they challenge the athlete ("don't settle - one more rep!"), and they are there to help the athlete when needed (providing physical and psychological safety if things go sideways).

To fully understand the impact of this role, look to the research. Think about moderate weights where athletes can do multiple repetitions. On average, when an athlete has a spotter, they will do at least 4 more repetitions than they will do without a spotter. Encouraging athletes, challenging athletes, and helping athletes makes a massive difference! It is important to note that in the research study the athletes lifting the weights received NO actual help with the weight. They did all the work themselves, but the presence of the spotter helped them raise their level.

No matter what sport you are involved in, it's not enough to just do one of these three things if you are going to help a high-performance athlete raise their level. Yes, you need to encourage them, but you also need to challenge them, and you also need to be there to help them - to have their back if things go sideways. The sky is the limit for athletes who have these types of people working with them! 😀

This coach description of an actual high-performance athlete accurately captures the approach embraced by many high-performance athletes in many sports. Losing sucks but it serves as a catalyst and a reminder to put in the work to get better.

Former all-star major league pitcher David Price said that if you are tired of the negative emotions that come along with losing put in the work to play better. World-class American distance runner Sara Hall said that strong opponents are not a threat but a source of inspiration - reminding you that there are higher levels to strive for.

This "put in the work to get better" mentality has been applied in many areas of life. A classic line that speaks to this work ethic is "better to light a candle than to curse the darkness."

Bottom line - all high-performance athletes want to play better, but they don't all want to put in the work to play better. As one high-performance coach said, "everyone wants to win, but not everyone wants to put in the work to give themselves the best chance to win."

It's okay to not want to put in the work, it's just that this is not consistent with being in high-performance sport. Putting in the work comes with the territory in high-performance sport. If you don't want to do it you have my 100% support - but then it is important that you join the non high-performance sport population who simply participate for fun, fitness, social benefits and to scratch the competitive itch. They are putting in the work in other areas. High-performance athletes are putting in the work in their sport to get as good as they can get in their sport. Their coaches expect this of them, and they expect it of themselves. 🙂

Belief change takes place in discomfort. The number one belief change athletes need to make to enable themselves to focus on thriving in their sport experiences, as opposed to surviving their sport experiences, centres around how they define themselves.

If athletes define themselves by the outcome every sport experience becomes a threat because their athletic self-worth is riding on the outcome. If athletes define themselves by their willingness to fully invest, battle, and compete every sport experience becomes an opportunity to do just that - fully invest, battle, and compete.

The challenge for athletes is that to make this belief change requires them to engage in sport experiences they previously viewed as threatening, and, within these previously threatening experiences define themselves, not by the outcome, but by their willingness to fully invest, battle, and compete.

Doing this takes courage. If athletes wait until they no longer fear their sport experiences they will never start to make the belief change. As the quote by Vignola (2024) implies, courage is action in the presence of fear - not the absence of fear. Belief change takes courage, but it is a courage all athletes possess - they just need to choose to access it. 😀

I appreciated the opportunity to talk with @astra_academy technical director Moe Rtimi. The Beyond the Pitch podcast on youtube is available and a good opportunity to learn a bit about what is in my book Pursue The Best You. Available on Amazon, Chapters/Indigo and Barnes &Noble. Podcast at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PbD6s4AwWSU

Do you play your sport like you sing your favourite song? Or do you play your sport worrying about the outcome - thinking about the end of the song?

In the book Pursue The Best You we talk about what it means to play free. Every athlete wants to play free but they are not sure what it means or how it feels.

One of the most effective ways to help athletes is to use what are called perceptual mediators - images that the athletes' brains can relate to. These images are generated by analogies and metaphors that allow the athlete to quickly integrate the information and be impacted by it. Thinking about singing your favourite song is one of the images sport psychologist Dr. Jerry Lynch creates for the athletes he works with.

Think of being in Grade 1 and your teacher teaching you how to do a jumping jack. Your teacher could spend 30 minutes telling you how to do a jumping jack, or your teacher could spend 30 seconds demonstrating a jumping jack. Seeing the image of a jumping jack makes it much easier for you to learn.

If you are playing your sport like you sing your favourite song you are playing free. If you aren't it's probably because you are focusing too much on the outcome (the end of the song). Give yourself permission to define yourself by your willingness to fully invest, battle, and compete (not defining yourself by the outcome). Defining yourself by your willingness to fully invest, battle, and compete makes it easier for you to play free - to play like you sing your favourite song. 😀

Fully investing in training improves the proficiency of athletes one training experience at a time. Training is the time you spend "sharpening your axe."

If you don't sharpen your axe it is going to be very difficult to chop down the next tree you encounter. If you don't fully invest in your training it is going to be very difficult to elevate your level of proficiency and give yourself the best chance to achieve whatever outcomes you want to achieve.

I am a good example of this. I am a classic "bogey" golfer (which means I shoot an average score of 90 on a par 72 golf course). My best round this year is an 83 and my worst round is a 98 - I am almost always scoring somewhere near the middle of those two numbers.

I would love to break 80 and shoot a round in the 70's, but I don't practice enough - I don't spend enough time sharpening my axe. Therefore, for some reason I expect to chop the tree down faster the next time even though I am using the same axe!

Hopefully the quote on this post, and my golf experience makes sense to you, and elevates your willingness to fully invest in your training experiences. If you prioritize sharpening your axe, it becomes easier to cut down the tree. 😊

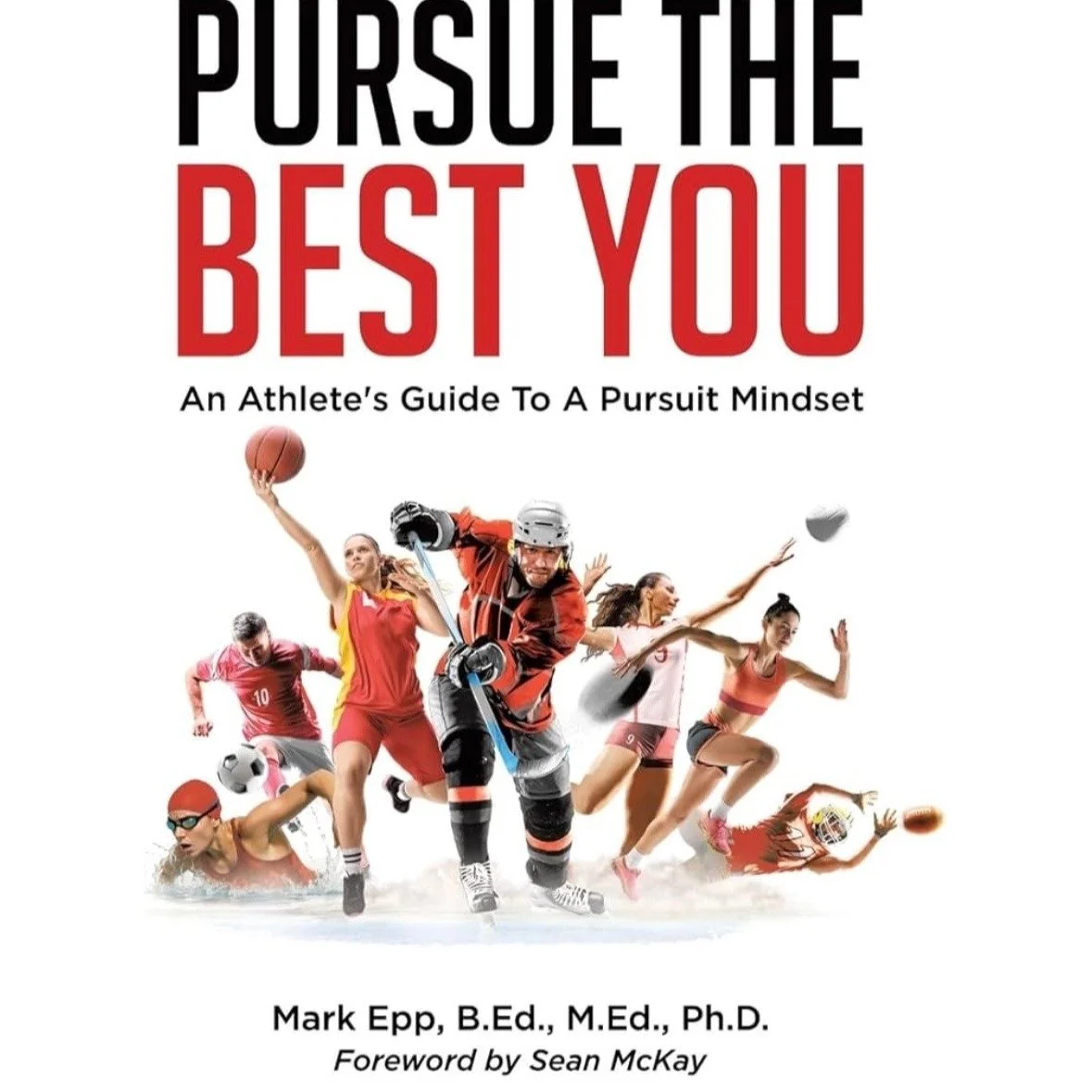

BIG NEWS!! “Pursue The Best You – An Athlete’s Guide To A Pursuit Mindset” is ready and available to help athletes!

I genuinely hope all athletes have a chance to read this little book because it talks about building healthy athlete beliefs and playing free. Healthy athlete beliefs and playing free generate a “win/win” for athletes – they enhance the quality of athlete sport experience, and they enhance athlete performance.

In conversations with coaches and athletes over the years I have heard that we need a sport mental training resource specifically written for athletes – a little book athletes can comfortably read in its entirety or target specific sections that have most relevance for them. A little book athletes can easily put in their backpack, gym bag, or set on the nightstand in their room.

To meet this need, I decided to write this book. It has now been published and is available in paperback form from major book distributors - Amazon.ca, Chapters/Indigo, Barnes and Noble.

I hope all athletes can experience healthy athlete beliefs and playing free. Research, along with my professional experiences working with athletes, has shown they are attainable. I hope that you consider purchasing this sport mental training resource. I truly believe it is “a little book all athletes should read”.

Sincerely,

Mark Epp

To maximize your potential as an athlete it is very important that you come to believe the above-mentioned statement.

Beliefs are the underlying assumptions people hold about themselves, others, and the world. Beliefs act as the lens through which people interpret experiences and situations.

Athletes who believe they are defined by the outcome do not play free. They play the score and not the game. They find it difficult to, as golfers say, "commit to the shot."

Athletes who believe they are defined by their willingness to fully invest, battle, and compete play free. They give each competitive moment "all of them." Not only is this approach more emotionally healthy, this approach also allows them to maximize the probability they will achieve the outcome they want.

Internationally-acclaimed growth mindset expert, Dr. Carl Dweck, made the following statement; "Mindsets are just beliefs. They're powerful beliefs, but they're just something in your mind, and you can change your mind."

I encourage you to switch your mindset from believing you are defined by the outcome to believing you are defined by your willingness to fully invest, battle, and compete. I am confident you will be happy with the effect this switch has on your sport experience! 😀

As we get older we begin to formulate what we believe about our sport experiences. When we are young what we believe about our sport experiences is largely shaped by those who's opinion of us matters most to us (e.g., parents).

This parental influence can be positive and generate healthy athlete beliefs. Unfortunately, this parental influence can also be negative and generate unhealthy athlete beliefs. The physiological reality is that our brains have the ability to learn and to store what we have learned, but this learning process does not distinguish between the development of healthy and unhealthy beliefs.

Athletes who are exposed, at a young age, to a lot of negativity from their parents attached to sport outcomes (e.g., level of play) develop the unhealthy athlete belief that they are defined by the outcomes of their sport experiences. This causes these athletes to be subjected to numerous negative outcome thoughts and forces them to try and play their sports through heightened levels of performance anxiety and fear of failure.

Athletes who are exposed, at a young age, to considerable parental support attached simply to the athletes' willingness to fully invest in their sport experiences, develop the healthy athlete belief that what defines them is their willingness to fully invest in their sport experiences. This enables these athletes to play free, focus on what they have control of, and know they will learn and grow (and be okay) no matter what the final outcome of the sport experience ends up being. 😀

It is true that pursuing your best self in your sport is first a psychological act before it is a physical act. You must first psychologically commit to the journey or you will never really get started.

However, once you have made this commitment the rest of the journey is measured by what you are actually DOING to pursue your best self in your sport. This could involve actions in any of the four foundational pillars of high-performance athlete development: physical, technical, tactical, and mental.

As a high-performance athlete, if this is a day where you have prioritized pursuing your best self in your sport, assess the day by what you actually DID during the day in your pursuit, not by what you intended to do. This approach will help maximize the efficiency and productivity of your athletic journey. 😀

Most people, myself included, play sports for any combination of the following four reasons: fun, fitness, social benefits, and to scratch the competitive itch. High-performance athletes share these reasons but they are also built for more: they are built to pursue their best self in their sport, and to absolutely battle and compete when they are in a competition.

If you consider yourself a high-performance athlete this comes with the territory. There is nothing wrong with not wanting to pursue your best self in your sport, and with not wanting to absolutely battle and compete in a competition. You can have a ton of fun playing sports until you are 90+ years old! You just shouldn't be playing high-performance sport, because high-performance sport requires participants who are built to pursue their best selves in their sport and absolutely battle and compete when they are in a competition. 😀

This statement by Joseph (2022) is important information for an athlete to consider. How you think dictates how you feel which influences how you act in competitive experiences. If you are feeling strong emotions that are compromising your competitive experiences (e.g, worry, fear, discouragement, uncertainty) ask yourself what thoughts are generating the challenging emotions.

Almost all the time, in competitive experiences, the athlete thoughts that produce challenging emotions are outcome-oriented in nature (e.g., “I suck because I made an error”).

As an athlete, make mastery your foundation, not outcome. Change your thought from “I suck because I made an error” to “I gave that moment all of me and I will continue to do so!”

This new thought triggers a positive “striving” feeling. It doesn’t guarantee you will get the outcome you want, but it maximizes your probability of getting it. 😀

As an athlete, achieving your dream depends on more than just you - it also involves factors outside of your control (e.g., a coach may not select you to be part of a particular team). However, "chasing" your dream is 100% on you. As the lyric from a well-known contemporary song states "If you have a dream, chase it, cause the dream won't chase you back."

For example, when in a team competition both opponents want to win the competition - this is their dream in the moment. Both opponents can't achieve this particular dream (only one opponent can win the competition), but both opponents can 100% chase the dream (do everything they can do to try and win the competition).

The key word is CHASE the dream. Achieving the dream depends on some factors outside of your control, but chasing the dream is all on you. 😀

Think of a glass of white milk that you are turning into chocolate milk by adding drops of chocolate syrup. Each drop that you add gradually turns the glass of white milk into a glass of chocolate milk. That is how training impacts playing in the sport experiences of a high-performance athlete.

High-performance athletes sometimes struggle with trying to figure out how much of their training mindset they need to bring into their competing mindset. This does not have to be a struggle. Athletes simply need to trust that their training will drip into their playing (just like the drops of chocolate syrup change the glass of white milk into chocolate milk one drop at a time).

As a high-performance athlete your training experiences are essential. These are the experiences where you are developing and refining your skills, and where you are expanding your tactical awareness of your sport. These training experiences require you to engage in what is called "deep practice" - a very focused attention to details and deliberate repetition of movement patterns and tactical decision-making that you are seeking to make part of your new normal.

However, when a high-performance athlete is in a playing/competing scenario, the goal is not to train, but to compete. In playing/competing scenarios (e.g., when someone is keeping score) it's all about battling and fulling investing ("immersing yourself in the competition"). If an athlete finds themselves feeling a little out-of-sorts or off-kilter they can always return to a key technical cue or tactical cue to remind themselves of what serves them well in their playing experience, but then get back to competing and battling.

The late NBA Hall-Of-Famer Kobe Bryant made a statement that captures the difference between a training mindset and a competitive mindset perfectly when he said, "I have never taken a shot in a game, that I did not take 10,000 times in practice." In practice he was working diligently on his shot - in the game he was playing free and just letting the ball fly! His training dripped into his playing. 😀